- Joined

- Sep 20, 2021

- Messages

- 152

Figured I would post this question in a separate thread, even though it's related to my other thread on fixing the toolpost - that's also in this section.

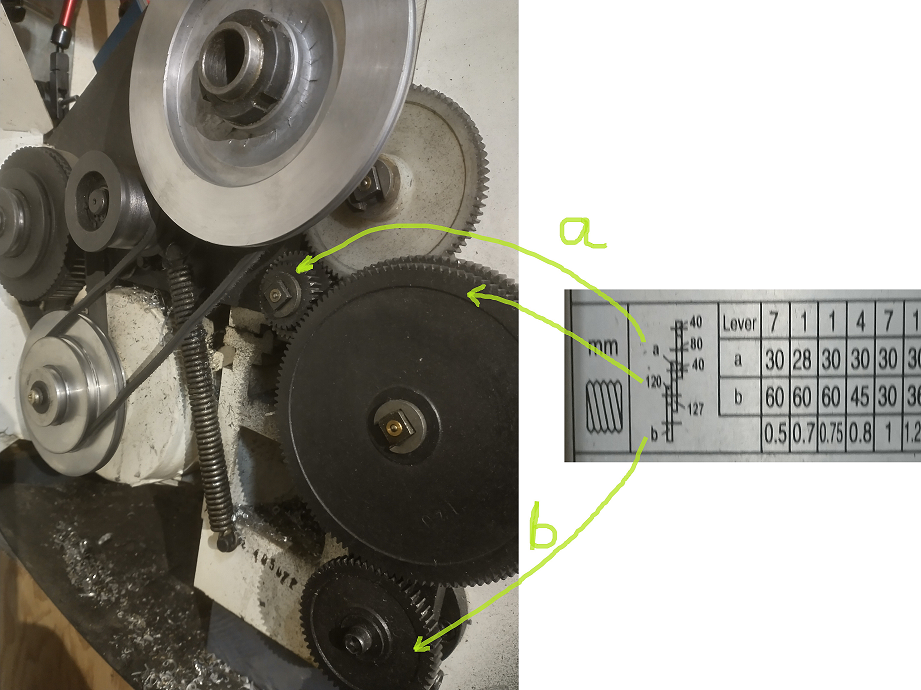

I'm trying to understand the threading chart on my Jet BD-920N. I've studied the manual and watched a couple of good videos on this subject. With that bit of knowledge I'm trying to understand what this chart is telling me about the gears in the back of my lathe. I need someone to confirm my understanding that the "a" and "b" gears in the picture on the right are the corresponding gears on the left with the arrows - if not, I'm gonna need you to straighten that out for me first.

Given the way those gears look I suspect that my lathe came setup by the previous owner for 'mm' metric threading.

I'm trying to understand the threading chart on my Jet BD-920N. I've studied the manual and watched a couple of good videos on this subject. With that bit of knowledge I'm trying to understand what this chart is telling me about the gears in the back of my lathe. I need someone to confirm my understanding that the "a" and "b" gears in the picture on the right are the corresponding gears on the left with the arrows - if not, I'm gonna need you to straighten that out for me first.

Given the way those gears look I suspect that my lathe came setup by the previous owner for 'mm' metric threading.

Last edited: