These are the things you learn in 30 years of machining that are hard to communicate. In cutting an Acme the way I described the high flank pressure especially are large Acme threads can sometimes cause the carriage to float and not cut much then all of a sudden dig in a bunch. Rest your left hand on the carriage hand wheel and cause some friction and it won't want to float.

-

Welcome back Guest! Did you know you can mentor other members here at H-M? If not, please check out our Relaunch of Hobby Machinist Mentoring Program!

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Choosing the right alloy steel - and make a quill

- Thread starter graham-xrf

- Start date

- Joined

- May 27, 2016

- Messages

- 3,471

That effect is just a bit subtle! I think it likely would not happen if the cut was the more usual straightforward kind, straight in at 90°, just getting deeper until the core diameter is reached.Rest your left hand on the carriage hand wheel and cause some friction and it won't want to float.

In your variation, with the slightly narrower 29° tool, I get it that when you are cutting on one side of the ACME thread at a time, the lathe lead screw has taken up the backlash without the benefit of anything to prevent "flopping back" a bit. I think you are saying to hold on to the carriage hand wheel as it travels, slightly "helping it along", so it does not drift back into "backlash space" - right?

I usually just rest my hand on the carriage wheel....which I’m guessing keeps it from flopping around. Just a tad bit of drag.That effect is just a bit subtle! I think it likely would not happen if the cut was the more usual straightforward kind, straight in at 90°, just getting deeper until the core diameter is reached.

In your variation, with the slightly narrower 29° tool, I get it that when you are cutting on one side of the ACME thread at a time, the lathe lead screw has taken up the backlash without the benefit of anything to prevent "flopping back" a bit. I think you are saying to hold on to the carriage hand wheel as it travels, slightly "helping it along", so it does not drift back into "backlash space" - right?

- Joined

- May 27, 2016

- Messages

- 3,471

Yes, of course it is. Backlash is taken out from a forward advancing thing by giving it some friction drag. Sorry about that.I usually just rest my hand on the carriage wheel....which I’m guessing keeps it from flopping around. Just a tad bit of drag.

Into the weeds I may be getting, and with apologies to MrWhoopee, I have been allowing myself to keep digging about thread turning, even to the extent of the advice on page 11 of the 1936 South Bend Lathe Works Bulletin No. 36A where one can get diverted by why we should use lard oil, or better still, lard oil with some sulphur added, for a smooth finish. (It's Christmas, and I've had a nice lunch)!

Try not to call me out on that Teddy R simplified the spelling in 1906 to read "sulfur", but I guess the message had not quite got through to Indiana 3 decades later - or maybe the county around South Bend voted Democrat, but I assure you that "sulphur" is the spelling used.

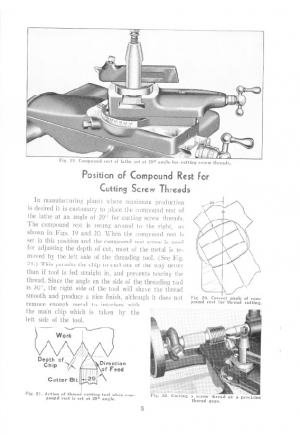

We pass by page 11, (backwards) where on page 8 there lurks this gem..

Now this is altogether different to the thread turning styles I have been seeing on YouTube, and discussing here. It seems halfway nearer to the BtoVin83 and Tim's method. The compound is rotated 29°, but note that the tool is actually ground 60° for 30° half-angle to the face of the cut.. Hmm.. hardly making sense when I look at the diagram, but anyway, the tool is advanced along to finish one side of the thread, the cut apparently getting thicker until one arrives at the other side, (and correct depth). The other side is made with the whole (here the left) side of the tool as it gets to depth.

OK - now I have got it! The tool angle is 1° beyond the 29° setting of the compound feed direction. The (right) side starts with a very small cut, and it stays quite thin, but always cutting more of the right side, because of the 1° wider tool always taking that bit more, instead of just rubbing along the already cut right side. When it arrives at depth, we have inevitably the full 60°. The way to get a shiny thread!

All earlier pages are about American National Screw Threads being 60°, and also grinding the tools 60°. I can see how the customary setting of the feed in direction to 29° would produce the nice finish. Is the choice of 29° influenced by the 1894 ACME 29° trapezoidal power thread design that predated the South Bend manual writers? Something must have motivated the choice of 29° from face to face for ACME threads. Nah - probably coincidence!

I have to admit, I kind of lost it when I came across the lard oil + sulphur. I can find weeds like no other! It cracked me up laughing. I am going to find some old bolt, and try this out (the cut method, not the lard)! But not yet. It was a great lunch, and 1 x 125ml glass of Prosseco, and I never do that! I don't want to make machinery turn, and reading measurements and doing arithmetic does not go as well as it should - spoils the mood even!

This whole discussion has made me want to have a go at cutting some ACME - so my thanks to all of you. This even if in the end (Oh - the shame of it!) I end up with store-bought 10x1/2" LH ACME, and a bronze nut import from McMaster-Carr, and a little pile of "attempts" awaiting the day they can join a meltdown!

Last edited:

- Joined

- Jan 20, 2018

- Messages

- 5,645

These are the things you learn in 30 years of machining that are hard to communicate. In cutting an Acme the way I described the high flank pressure especially are large Acme threads can sometimes cause the carriage to float and not cut much then all of a sudden dig in a bunch. Rest your left hand on the carriage hand wheel and cause some friction and it won't want to float.

I have had to use this same technique with coarser thread pitches. Very worn half-nuts may require a lot of drag to prevent "pitch wander", particularly at the beginning of the pass. I do it without even thinking now.

- Joined

- Jan 20, 2018

- Messages

- 5,645

I keep a copy of SB's "How to Run a Lathe" in the "reading room" for the sake of nostalgia and the occasional tidbit of overlooked info. Since I'm running an SB Heavy 10, it is particularly pertinent. I understand that bacon grease mixed with kerosene makes a good substitute for lard oil in certain situations, but I imagine it would drive me to the kitchen fairly quickly for a BLT.

In school, I was taught to set the compound at 29.5 deg., as if we could interpolate the graduations that closely. In addition to improved finish, it provides for better chip flow since there are not equal, competing chips coming off the tool. Many people poo-poo the whole notion and simply feed straight in. They seem to get equally good results, though it helps if you are using a newer, tighter and more rigid lathe.

I only recently became aware that TR was responsible for the simplified spellings used in the U.S. As these were not officially adopted, it probably took quite some time before "center" became the standard instead of "centre". I scarcely notice the spelling of "sulphur", as that's how it was spelled in my first chemistry set.

In school, I was taught to set the compound at 29.5 deg., as if we could interpolate the graduations that closely. In addition to improved finish, it provides for better chip flow since there are not equal, competing chips coming off the tool. Many people poo-poo the whole notion and simply feed straight in. They seem to get equally good results, though it helps if you are using a newer, tighter and more rigid lathe.

I only recently became aware that TR was responsible for the simplified spellings used in the U.S. As these were not officially adopted, it probably took quite some time before "center" became the standard instead of "centre". I scarcely notice the spelling of "sulphur", as that's how it was spelled in my first chemistry set.

Usually the size hobbiests make dragging the hand wheel is not a requirement, I'm talking about cutting 2-3 inch diameter 2 pitch Acmes and they can float a carriage. But the habit carries over and I find myself doing it without thinking. The idea is create drag on the carriage and forcing it to the backside of the half nut, now the carriage doesn't want to wander.

My dad taught me to cut the register for both internal and external acmes. That way when the tool touches off you know you are to proper depth. The tool is cutting on 3 sides until getting to depth that's true but when you widen it out with the compound you are only cutting on one side. Cutting a 3 inch 2 pitch Acme even following the flank of the screw can be give you fits.

- Joined

- May 27, 2016

- Messages

- 3,471

Only partly is the story so. Theodore was home schooled, and (hearsay), may have had a hard time with spelling. He was influenced by zealots with a mission to really mess with the spelling, and who were self-convinced and selectively rationalizing their obsession (Andrew Carnegie, Mark Twain et al.) The attempts to spell "fixed" as "fixt", "rhyme" as "rime", and similar extremes were headed off by Congress.I only recently became aware that TR was responsible for the simplified spellings used in the U.S. As these were not officially adopted, it probably took quite some time before "center" became the standard instead of "centre". I scarcely notice the spelling of "sulphur", as that's how it was spelled in my first chemistry set.

After attempts to "sneak the changes in and get them established in some Government documents, Congress forced that the right to mess with the language by Presidential order was disallowed. Hoping to get re-elected, Teddy abandoned the attempt. The Congress action had already set out that Webster's and other accepted dictionaries be used. These change over time, so some of the more obvious phonetic spellings did get adopted - except, it seems, by the writers of the South Bend Lathe Works publications. It may have been a generational thing. Some may have been at school before Webster's and others had moved on.

P.S. I have been trawling through the drawers of the SB9C bench (that came with the lathe), and what do I find? About 14" long bar of 1" brass-looking material. Brass, bronze, phosphor-bronze, tin-bronze, who knows? Too late that I already ordered the quill material, including the bronze for the ACME nut. Oh well. If you do what we do, you can't ever be too rich, and you can't have too much spare 1" rod material.

- Joined

- May 27, 2016

- Messages

- 3,471

THE QUILL CONSTRUCTION PLAN (sort of)

I am thinking through the sequence for making the quill.

1. Face off both ends, and give them centres.

2. Get one end into a 4-jaw, and the other onto a MT2 (dead?) centre, and turn a quill length to outer size.

We notice here that the older lathe (about 1938 or so) has a slightly thicker quill.

The worn target quill measures 1.055" (26.79mm) and the SB-9C quill measures 1.070" (27.178mm)

The fatter one does not fit up the thinner tailstock. It raises a question.

Does one machine a new quill to 1.055, or should there be an attempt to "fit" it, making the final cut such that it slides in snug, perhaps compensating for tailstock wear?

3. We use a MT2 shank drill set direct into the tailstock, avoiding using a tailstock chuck . A little unsure of the size here. For quills with a bronze nut back there, the through drill hole does not have to be smaller than the internal ACME 2G 1/2" x 10 Minor diameter 0.4000", so we are OK with the smallest hole the taper needs to have at the back. We need it good for a MT2, at a depth where the proper amount is sticking out the front of the quill.

Apparently the depth should be 2" + 39/64ths deep. The small end down there is apparently 0.572" but I still have to figure out how a taper per inch of 0.04995 x 2.60975" = 0.13034" gets us to 0.572". There are tolerances, and 0.5696 is -0.0023" adrift.

The tables are a bit confusing. OK - so we get a hole deep enough to part into later.

The drill looks like it needs to be 9/16" as a starter, and it has to be long enough

4. We bore out most of the taper, done with much trawl of YouTube. I am sure there is a "best" way to do this, and I hope folk will tell.

We open it more with a MT2 HSS cutter, with the back of the cutter supported in a tailstock dead center, and carefully using a spanner to turn it, keeping the whole lot together with a little squeeze from the back. Use cutting oil, and make sure we don't cut too deep, allowing the reamer is to follow. How close do we go?

Follow with the finishing reamer. Again, we stop short of making it too deep. Stop where a MT2 anything is supposed to end up.

5. We part it off at the correct length. Then turn it around, re-chuck it, and drill the wider hole into the back, just deep enough to accept the bronze nut, which was made/acquired in a separate operation.

7. We fit the bronze nut, and secure it with 2 more holes, like the one the SB-9C has, or we use 3 holes at 120° apart, tapped to secure a flange on the bronze nut. Glue in with Loctite as well.

8. Chuck again at the nut end, and put an MT2 arbor into the taper to enable to support the other end in a tailstock chuck. Mount a tool ground to be as wide as the quill slide anti-rotation slot, and set it on it's side. Apparently 0.185" wide. Was that an attempt at 3/16"?

Is the quill slot supposed to be slightly wider at the top than at it's depth? Does the cutter have to have a slight trapezoid shape? Not known yet, but I will find out.

Anyway, with the tool at the right height, we repeatedly move the saddle across, with little planing cuts, to eventually scoop out 0.1" deep from the full radius start point. Alternatively #1, we consider some way to mount it up, and use a MT3 milling cutter in the spindle. Alternatively #2, we take it to the friend, who is member of a model engineering club, where it finds it's way to a Bridgeport mill.

9. There is a final little groove, a bit roughly scooped out on the side opposite to the full length slot, at the nut end. It is 0.1" wide, 1.2" long starting from where it finds it's depth, which is not much. Is than an oil channel?

The same groove on the SB9C quill is only 0.08" wide, and much better made, looking "engraved". I am thinking that whatever method was good for the main slot will also be OK for the little one.

This is, of course, just a first think-through, and I fully expect some bits may have been left out, or in the wrong order, or simply not a good plan in the first place. If anything spectacularly crappy happens, I will post it anyway. For all I know, maybe someday, someone who has never done it before will come across it, and see the advice from those with 30+ years experience, after they figured out how to type while laughing!

I am thinking through the sequence for making the quill.

1. Face off both ends, and give them centres.

2. Get one end into a 4-jaw, and the other onto a MT2 (dead?) centre, and turn a quill length to outer size.

We notice here that the older lathe (about 1938 or so) has a slightly thicker quill.

The worn target quill measures 1.055" (26.79mm) and the SB-9C quill measures 1.070" (27.178mm)

The fatter one does not fit up the thinner tailstock. It raises a question.

Does one machine a new quill to 1.055, or should there be an attempt to "fit" it, making the final cut such that it slides in snug, perhaps compensating for tailstock wear?

3. We use a MT2 shank drill set direct into the tailstock, avoiding using a tailstock chuck . A little unsure of the size here. For quills with a bronze nut back there, the through drill hole does not have to be smaller than the internal ACME 2G 1/2" x 10 Minor diameter 0.4000", so we are OK with the smallest hole the taper needs to have at the back. We need it good for a MT2, at a depth where the proper amount is sticking out the front of the quill.

Apparently the depth should be 2" + 39/64ths deep. The small end down there is apparently 0.572" but I still have to figure out how a taper per inch of 0.04995 x 2.60975" = 0.13034" gets us to 0.572". There are tolerances, and 0.5696 is -0.0023" adrift.

The tables are a bit confusing. OK - so we get a hole deep enough to part into later.

The drill looks like it needs to be 9/16" as a starter, and it has to be long enough

4. We bore out most of the taper, done with much trawl of YouTube. I am sure there is a "best" way to do this, and I hope folk will tell.

We open it more with a MT2 HSS cutter, with the back of the cutter supported in a tailstock dead center, and carefully using a spanner to turn it, keeping the whole lot together with a little squeeze from the back. Use cutting oil, and make sure we don't cut too deep, allowing the reamer is to follow. How close do we go?

Follow with the finishing reamer. Again, we stop short of making it too deep. Stop where a MT2 anything is supposed to end up.

5. We part it off at the correct length. Then turn it around, re-chuck it, and drill the wider hole into the back, just deep enough to accept the bronze nut, which was made/acquired in a separate operation.

7. We fit the bronze nut, and secure it with 2 more holes, like the one the SB-9C has, or we use 3 holes at 120° apart, tapped to secure a flange on the bronze nut. Glue in with Loctite as well.

8. Chuck again at the nut end, and put an MT2 arbor into the taper to enable to support the other end in a tailstock chuck. Mount a tool ground to be as wide as the quill slide anti-rotation slot, and set it on it's side. Apparently 0.185" wide. Was that an attempt at 3/16"?

Is the quill slot supposed to be slightly wider at the top than at it's depth? Does the cutter have to have a slight trapezoid shape? Not known yet, but I will find out.

Anyway, with the tool at the right height, we repeatedly move the saddle across, with little planing cuts, to eventually scoop out 0.1" deep from the full radius start point. Alternatively #1, we consider some way to mount it up, and use a MT3 milling cutter in the spindle. Alternatively #2, we take it to the friend, who is member of a model engineering club, where it finds it's way to a Bridgeport mill.

9. There is a final little groove, a bit roughly scooped out on the side opposite to the full length slot, at the nut end. It is 0.1" wide, 1.2" long starting from where it finds it's depth, which is not much. Is than an oil channel?

The same groove on the SB9C quill is only 0.08" wide, and much better made, looking "engraved". I am thinking that whatever method was good for the main slot will also be OK for the little one.

This is, of course, just a first think-through, and I fully expect some bits may have been left out, or in the wrong order, or simply not a good plan in the first place. If anything spectacularly crappy happens, I will post it anyway. For all I know, maybe someday, someone who has never done it before will come across it, and see the advice from those with 30+ years experience, after they figured out how to type while laughing!

Last edited: